|

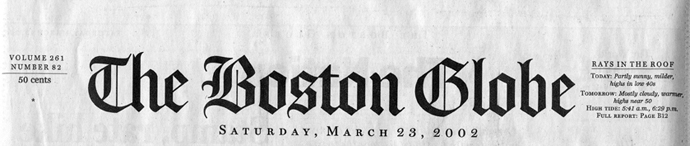

Zora Arkus-Duntov: The Legend Behind Corvette

by Jerry Burton

Price: $49.95

|

Boston Globe, March 23, 2002

How he made Corvette an icon ?

What if?

After falling through the ice on a frozen canal in St. Petersburg, Russia, he hadn't been able to use his fists and upper body to ice-break his way back to shore? The Gypsies had been right and he had died young?

He had not escaped the Nazis for America?

He had not wandered into that General Motors Motorama in New York City and spotted a prototype sports car whose looks dazzled him?

What if?

We may well never have had the Corvette, the true American sports car.

If you are a fan of the Corvette, of sports cars, of engineering, of racing, you need to read ?Zora Arkus-Duntov: The Legend Behind Corvette,? by Jerry Burton (Bentley Publishers, Cambridge).

While Harley Earl, head of GM's design staff at the time, invented the Corvette, it is Arkus-Duntov who is credited with saving and refining it.

Arkus-Duntov's is an amazing tale of a Bolshevik boy who witnessed the Russian Revolution in 1917, attended a top German technical school, served in the French Air Force, escaped Nazi-occupied France for the United States, became a consultant for the US military, started a munitions company, helped develop an atomic compressor ? and the went looking for real work.

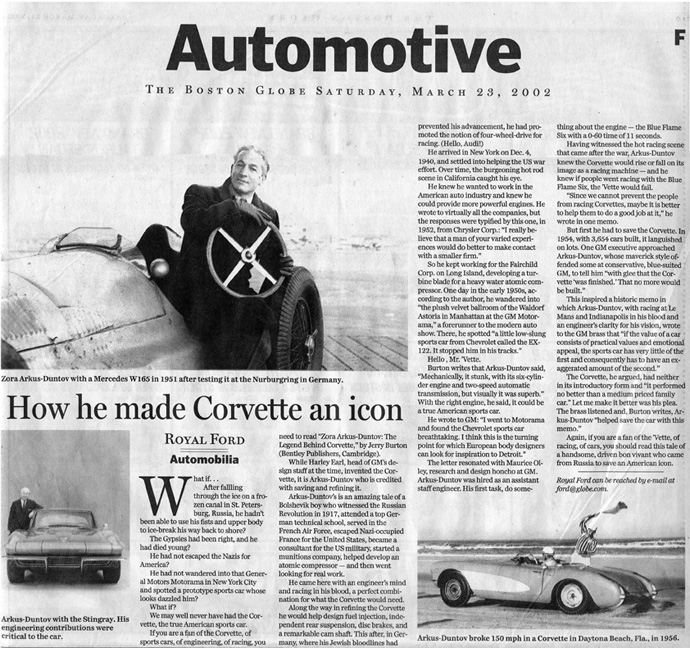

He came here with an engineer's mind and racing in his blood, a perfect combination for what the Corvette would need.

Along the way in refining the Corvette he would help design fuel injection, independent rear suspension, disc brakes, and a remarkable cam shaft. This after, in Germany where his Jewish bloodlines had prevented his advancement, he had promoted the notion of four-wheel-drive for racing. (Hello, Audi!)

He arrived in New York on Dec 4., 1940, and settled into helping the US war effort. Over time, the burgeoning hot rod scene in California caught his eye.

He knew he wanted to work in the American auto industry and knew he could provide more powerful engines. He wrote virtually all the companies, but the responses were typified by this one, in 1952, from Chrysler Corp: ?I really believe that a man of your varied experience would do better to make contact with a smaller firm.?

So he kept working for the Fairchild Corp. on Long Island, developing a turbine blade for a heavy water atomic compressor. One day in the early 1950's, according to the author, he wandered into ?the plush velvet ballroom of the Waldorf Astoria in Manhattan at the GM Motorama,? a forerunner to the modern auto show. There he spotted ?a little low-slung sports car from Chevrolet called the EX-122. It stopped him in his tracks.?

Hello, Mr. ?Vette.

Burton writes that Arkus-Duntov said, ?Mechanically, it stunk, with it's six-cylinder engine and two speed automatic transmission, but visually it was superb.? With the right engine, he said, it could be a true American sports car.

He wrote GM: ?I went to Motorama and found the Chevrolet sports car breathtaking. I think this is the turning point for which European body designers can look for inspiration to Detroit.? The letter resonated with Maurice Olley, research and design honcho at GM. Arkus-Duntov was hired as an assistant staff engineer. His first task, do something about the engine ? the Blue Flame Six with a 0-60 time of 11 seconds. Having witnessed the hot racing scene that came after the war, Arkus-Duntov knew the Corvette would rise or fall on its image as a racing machine ? and he knew if people went racing with the Blue Flame Six, the ?Vette would fall.

?Since we cannot prevent the people from racing Corvettes, maybe it is better to help them to do a good job at it,? he wrote in one memo.

But first he had to save the Corvette. In 1954, with 3,654 cars built, it languished on lots. One GM executive approached Arkus-Duntov, whose maverick style offended some at conservative, blue suited GM, to tell him ?with glee that the Corvette was finished. That no more would be built.?

This inspired a historic memo in which Arkus-Duntov, with racing at Le Mans and Indianapolis in his blood and an engineer's clarity for his vision, wrote to the GM brass that ?if the value of a car consists of practical values and emotional appeal, the sports car has very little of the first and consequently has to have an exaggerated amount of the second.?

The Corvette, he argued, had neither in its introductory form and ?it performed no better than a medium priced family car.? Let me make it better was his plea. The brass listened and, Burton writes, Arkus-Duntov ?helped save the car with this memo.?

Again, if you are a fan of the ?Vette, of racing, of cars, you should read this tale of a handsome, driven bon vivant who came from Russia to save an American icon."

-Royal Ford

![[B] Bentley Publishers](http://assets1.bentleypublishers.com/images/bentley-logos/bp-banner-234x60-bookblue.jpg)